Our Beginnings

With mass scale displacement of Tamil, Muslim and Sinhala families from the North and East in 1990, to different locations such as Puttalam and Colombo, Suriya Women’s Development Centre was set up to deal with the special needs of women in the welfare centres located in and around the capital city. Together with activist sisters in Colombo and women from the Poorani Women’s Development Centre – Jaffna, work began in the refugee camps. Suriya responded to the very practical gender specific needs of women and children and supported them to cope with the challenges of loss, fear and managing life in a new environment. Suriya organised mobile health clinics, held peace-building workshops for children and used cultural activism to support and mobilise women. In 1993 the camps were moved to Batticaloa in the Eastern Province and some of these pioneering activists took the bold decision to relocate with them.

Suriya currently acts as a voice of and for women living in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka and plays an active role in bringing to the forefront the perspectives of all women. Suriya is committed to working with and for women from Tamil and Muslim communities through gender empowerment, development and cultural programs. We aim to create an equitable and peaceful society free of discrimination against women. Suriya’s vision is to “build a society which is non-discriminatory, free of violence and respects and treats women with equality and dignity”.

Our Philosophy

Suriya’s work is based on a social justice approach which aims to create an equitable and peaceful society. As the feminist theorist, Naila Kabeer, articulates this includes working towards freedom, equality, tolerance and solidarity. This means directly addressing social exclusion and marginalisation of women in terms of economic rights, ethnic identities, violence and abuse, poverty and voice.

Globally, it is recognised that universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based upon social justice. Therefore, in order to ensure women’s rights and justice in a post conflict context we have developed an integrated approach that addresses violence against women and human rights, along with women’s empowerment and economic rights, as well as working on identity politics and culture.

Our work incorporates interventions at the individual level with work done to change discriminatory socio – cultural norms, as well as to bring about structural change and policy/legal reform.

Our Context

Batticaloa District is one of the districts with a high level of poverty and high numbers of migrant workers. Many women seek foreign employment as housemaids in the Middle East. Unable to meet their basic needs many others have taken high interest loans and are unable to meet their debt repayments.

Thirty years of armed conflict has greatly impacted on women’s lives. Multiple displacement and loss of assets, loss of family members due to the conflict, disappearances and arrests, high numbers of women headed households (more than 23.4% of households in Sri Lanka are now headed by women), loss of livelihoods, underage marriages and child pregnancies are some of the challenging issues faced by women in Batticaloa.

Violence against women and children has also become a grave issue in Sri Lanka. High incidents of rape and incest are reported nationally. Our impression is that even though the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act (PDVAct) was passed by the Sri Lankan Parliament in 2005, the incidents of violence within homes and communities are increasing. In the post war context, this could be due to increased awareness and support networks being put in place, however, we also see a strong continuum between the violence against women and girls during conflict and afterwards, resulting from normalisation of violence and brutalisation of communities over a 30 year war.

In the context of increasing poverty, lack of sustainable livelihood options for women and loss of assets women have had little opportunities and are powerless to leave abusive relationships or take action against perpetrators of violence.

Compounding decades of war, came the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami which devastated the region. The largest number of casualties in Batticaloa were women. Many drowned in an attempt to rescue their children and running was made difficult in a saree where metres of fabric, together with the women’s long hair, often got tangled in the debris. Though its been close to a decade since the Tsunami disaster, the gendered impacts continue in terms of increasing poverty, loss of livelihoods and increasing violence.

Our Structure

Suriya has an Executive Director working collaboratively with 17 Staff, 9 Coordinating Committee Members and 4 Advisory Board Members. Our committed Staff of women are the backbone of Suriya and their skills, creativity and care, offer continual support to all those who seek our assistance.

Over the years it is the women who directly benefited from our activities who have now taken key leadership positions within the organisation. Key coordinator positions are held by women leaders from our village women’s groups. The legal work is now done by women who initially came to Suriya as survivors of violence. Similarly, women who were part of the village women’s cultural groups now create and lead the cultural activism of Suriya.

The Coordinating Committee are women from the district who are committed to promoting women’s progress and development in the District. They volunteer their time to meet with the Staff monthly to review programs, plan and guide decision making processes.

The Advisory Board is comprised of members who work for women’s rights in national and international forums and who meet each year with the Coordinating Committee and Staff at the Annual General Meeting.

Our Space

Our main office is situated in a beautiful old home on Lady Manning Drive overlooking the Kallady Bridge and lagoon. A small thatched hut on the premises is where we hold our more informal meetings. Cultural programs take place under the shaded canopy of trees on the grounds outside of our office.

In recent years we acquired 1.5 acres of land in Mylambaveli, just north of Batticaloa town, which is in the early stages of development – a women’s collective will utilise a portion of this land for their livelihood activities.

Suriya had the first woman auto driver in Batticaloa! Our three-wheeler is brightly designed to reflect the images of women from all ages and backgrounds with whom we work. It is widely used in our public education campaigns and advocacy programs to promote women’s rights – “Women Can Do Anything”!

Our Donors

We wish to acknowledge the following donors and friends who have supported Suriya’s work over the years:

- Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA)

- Cordaid

- Diakonia

- Ford Foundation

- Neelan Thiruchelvam Trust (NTT)

- FORUT

- Global Fund for Women (GFW)

- HIVOS

- Italian Foundation

- Oxfam Australia

- Primates World Relief and Development Fund (PWRDF)

- South Asian Women’s Fund

- USAID /MSI

- United Nations Development Fund (UNDP)

- Urgent Action Fund (UAF)

- Women and Media Collective (WMC)

- World University Services of Canada (WUSC)

- FOKUS Women

- All our individual donors

Our Sisters

Remembering Sunila Abeysekera….article which appeared in the Law and Society Trust, Volume 24 Issue 313,314. Novermber & December 2013

Vaasam……. remembering you

Suriya Women’s Development Centre – Batticaloa

This is a collective effort to remember Sunila. This article is a compilation of informal discussions among women who have been part of Suriya and Poorani Women’s Centres since 1991. We talked about her support for human rights work, peace work, women’s rights work, capacity building of women activists, fund raising for local women’s groups, her love, her strength and her warmth.

Sunila’s involvement with the Poorani women…..

Sunila used to come to Jaffna in the early 1980s, she used to come with Charles Abeysekera, her father, and the Movement for Inter racial Justice and Equality. Sunila also came for the funeral of Rajani Thiranagama. She came with her son, Sanjaya, in 1989.

At that time the women who were involved in the Poorani Centre got to know Sunila. Poorani was a safe space and training centre for women who were affected by the war. In 1991, Poorani was taken over by the LTTE. The LTTE women were pressuring them to give the Poorani funds for their work. The Poorani women decided to return the money to the donors, so they closed the centre and moved to Colombo.

As one former member of Suriya noted when she spoke at an event organised in Canada this year “During the 1990s, I was forced to leave Jaffna because of the unsafe situation there. Registration with the Police was difficult in Colombo. Sunila would come with me to the Police and it would make things much easier for me. At this time, large numbers of Tamils and Muslims were displaced from the North-East of Sri Lanka to Colombo. I remember the time I was arrested in 1992 and she came to the Police station to help get my release. These things happened often in Colombo and Sunila was always there to help us”.

Others also recalled this time – “during this time four Poorani women and some of their family members were arrested by the Dehiwala Police and kept in the jail there for 3 weeks. We were trying to set up a group of people to organise food. We organised a mixed group – foreigners, Muslims, Tamils, Sinhalese men and women. So the Police were aware that many people knew about this case and were interested in what was happening to them. We had heard that women were raped in the Police stations and were very worried for the protection of these women. Sunila was very active in getting these women released”.

There were many discussions among women activists who had been displaced from the North and activists based in Colombo like Sunila. As one founder member of Suriya recalled “we took an auto and went around to various camps where displaced people from the North and East stayed. We had long discussions about what we could do. At that time EPDP was in charge of the camps. We started negotiating with them about food rations and other basic services for women. We didn’t have an office. We got a small space at the back of the Women and Media Collective office where we started working”.

Sunila’s politics….

Sunila lived what she stood for. Her life reflected her values of democracy. Her life was her message. Among Tamils and Muslims of this country she was never seen as an outsider. She had many friends among different communities. She made frequent visits to the North and East even during the hardest times for travel. She had traveled to the remote villages to collect stories of those affected. This gave a human dimension to her documentation of human rights violations. She maintained a view that the cause for ethnic conflict is the denial of equal rights and dignity to one ethnic group. She had dreamt about Sri Lanka as a country where rights of all citisens are respected and democratic practices are upheld. She had viewed the ethnic issue from a democratic perspective. She never accepted the concepts of majority, minority. For her, all individuals should have freedom and rights. In Sunila’s politics she highlighted the rights abuses committed by the State under the Prevention of Terrorism Act and Emergency regulations. She also denounced violations by Tamil armed groups including the LTTE. Sunila had to pay the price for her unwavering defense for the rights of Tamils. She was branded as a traitor of the country and had to face threats to her life. She had always talked about a political solution to the ethnic issue. She denounced violence and militarism. She brought a feminist perspective into peace building.

Journeys – some glimpses of her human rights work…..

She was involved in documenting disappearances in the East from 1987 onwards. She didn’t just come to the town areas. She made many visits into rural villages. In 2008, when people were sent back to their villages after being displaced for many months, there were rumours about women being raped, especially women living alone. There were rumours of women being sexually harassed during round ups and house to house checks in the nights. Sunila visited during this time. She stood as the frontline voice and face and negotiated with the military to gain access to these areas in internal Batticaloa. She provided protection and cover for local women activists.

Another woman recalled “I remember her work post tsunami. She was the one who pushed for citizens’ committees for people to give testimonies after the tsunami disaster. She brought a rights-focus into post tsunami reconstruction. She would sit the whole day on people’s tribunals listening to person after person, never stopping them until they finished what they had come to say.”

In one of her last visits to Batticaloa in 2011, she wanted to visit the Kathiraveli school where displaced families had stayed and was damaged by shelling in 2006. She was ill by this time. But still she travelled.

She always took care of people……

When someone was sick she bought them food and kept them in her house. It wasn’t just work for her, she embodied those things she wrote and talked about. She really lived it. She gave her time and had very strong personal connections and gave personal care. When some of the women from Suriya went to international forums for the first time, she always took care of them. Discussed their presentations and gave guidance on how to be careful and what issues to raise. She always gave confidence for local women to speak at international events. She took women shopping, to the night markets, site seeing, to experience new food.

From bus stops to police stations…..she was the one to call….

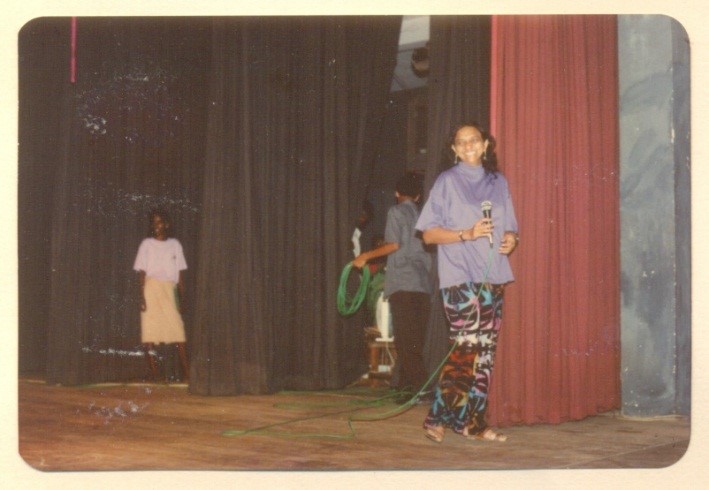

Once when the cultural group went to Colombo for a performance at the SLFI, the girls had gone outside for sightseeing and had taken some photographs of the public library. This was 1997. The police came and arrested the woman leader of the cultural group. Sunila immediately took steps to negotiate with the police and calm down the other members of the cultural group who had gone for the first time to Colombo to perform.

As another woman activist recalled “I used to be a person who didn’t travel much. In 1996 I just joined Suriya as a board member. I was invited to make a presentation on women’s health in Induruwa. I was from Jaffna, living in Batticaloa. 13 check points to pass to reach Colombo. Sunila promised to pick me up in Colombo. I arrived at 10.30 in the night. I was inside a small Tamil tea shop in Petta. I was waiting for her. I had a cup of tea. I was really panicking. Then suddenly she arrived in a van full of women. She had already picked up many other women. She was leaning out of the window asking if there is a Tamil women waiting in the shop. Her voice when I heard it gave me the confidence. The shop people didn’t want to let me go with a bunch of women, without a man! She got down from the van and talked with them. She taught me how to break barriers within myself – about the fear of darkness, and about fear of mobility.

Mentoring women and local women’s organisations….

She always gave new ideas. Even when she was quite seriously ill she sent her comments for the Suriya AGM or wanted to skype in. She was actively involved in whatever way she could. She brought international debates and feminist ideas into our discussions, so we could guide our own work with what was happening internationally. She also pushed women to participate and speak in international forums. She always found a way to bring together people with different perspectives and different backgrounds. Sunila has trained many generations of women at Suriya and in the East through the SANGAT South Asian Gender Training Programme. She has also supported local women’s organisations through fund raising and endorsing for proposals. For example, when the women’s crisis centre in Batticaloa, had run out of funds and was desperately looking for funds to not close down, Sunila mobilised international funds and recommended the centre to be supported.

For all these memories, and many untold ones, we dedicate this poem to Sunila and to deep friendship…

It was a sharing

Wholesome and truthful

Being you and I,

under the glassy sky……………..

You laughed

recalling the magical moment

when your nest was brimful

spilling with honey……

As we drink endlessly

the night

thirsty of the two

drifts away

having tasted

the unsurpassed wonder.

Then, you and I

under the endless glassy sky.

Anar, “Two Women”, Let the Poems Speak, SWDC 2010